|

|

|

Translate this page in your preferred language:

|

| REPRODUCTIVE MANAGEMENT: |

| Back |

Breeding of heifers:

- Regardless of age, puberty is reached when a heifer weighs approximately 40% of her mature body weight.

- Breeding however, is recommended when a heifer has reached 60% of her expected mature body weight.

This is normally achieved when the heifer is 14 to 16 months old.

- Smaller breeds may be bred one or two months earlier than large breeds because they mature faster.

- Heifers in good condition and gaining weight at breeding time generally show more definite signs of estrus and have improved conception rates over heifers in poor condition and/or losing weight.

- Over-conditioned or fat heifers have been reported to require more services per conception than heifers of normal size and weight.

HEAT DETECTION :

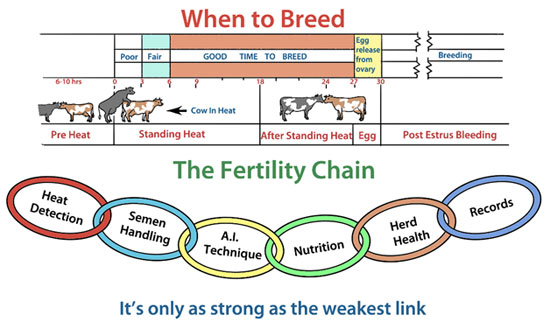

This is an extremely important exercise as a missed heat translates into a wasted 21 days while efficient heat detection makes it possible to serve the animal at the right time.

The average heat interval is 21 days with a range of 18 to 24 days. Duration of heat is 24 to 36 hours in exotic and crossbred cows. Several methods are used to detect heat. The most commonly used by farmers are behavioral signs and physical changes.

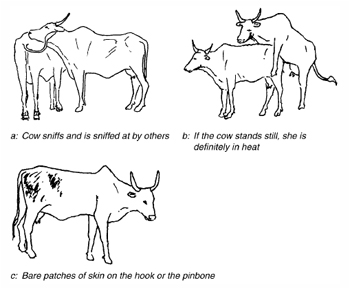

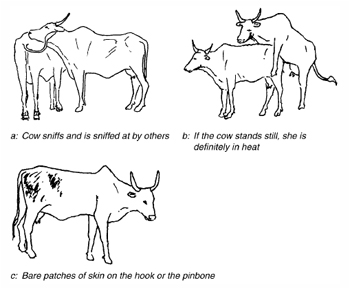

1. Early Heat: watch the animal closely.

- Increased nervousness/restlessness.

- Mounting other cows.

- Swollen vulva.

- Licking other cows.

- Sniffing other cows and being sniffed.

- Reduced feed intake.

2. Standing Heat: take the animal for service.

- Standing to be mounted.

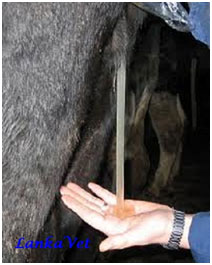

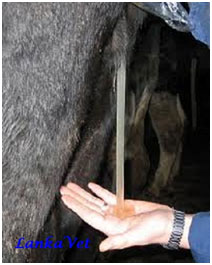

- Clear mucus discharge.

- Sharp decline in milk production.

- Tail bent away from the vulva.

- The animal may stop eating.

3. After heat: keep records.

- Dried mucus on the tail.

- Roughened tail head.

- The animal refuses to be mounted.

- Streaks of saliva or signs of leaking on her flanks.

SYMPTOMS OF HEAT:

The various symptoms of heat are

- The animal will be excited condition.

- The animal will be in restlessness and nervousness.

- The animal will bellow frequently.

- The animal will reduce the intake of feed.

- Peculiar movement of lumbo-sacral region will be observed.

- The animals which are in heat will lick other animals and smell other animals.

- The animals will try to mount other animals.

- The animals will standstill when other animal try to mount. This period is known as

standing heat. This extends 14-16 hours.

- Frequent micturition (urination) will be observed.

- Clear mucous discharge will be seen from the vulva, sometimes it will be string like mucous will be seen stick to the near the pasts of vulva.

- Swelling of the vulva will be seen.

- Congestion and hyperarmia of membrane.

- The tail will be in raised position.

- Milk production will be slightly decreased.

- On Palpation uterus will be turgid and the cervix will be opened.

|

|

|

|

|

|

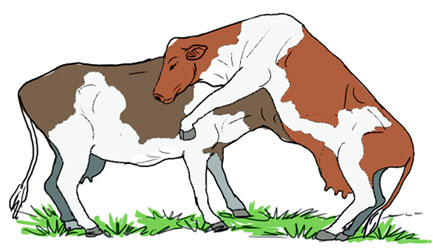

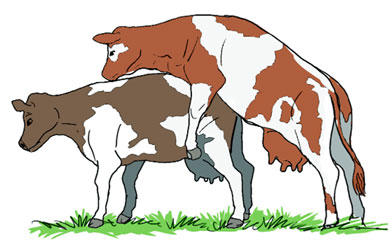

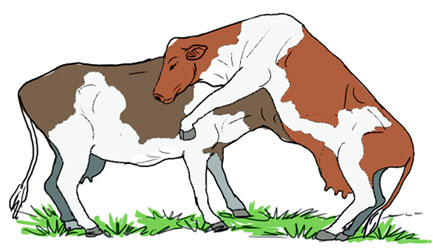

| (a) Standing to be mounted: The positive sign of heat is standing to be mounted. The cow in heat stands to be mounted and does not move away. |

|

(b) Licking: Both cows may be in heat. |

|

(c) Mounting head to head:

The cow mounting is in heat.

|

|

|

Fig. (a) to (c): Behavioral signs of heat in cows. |

|

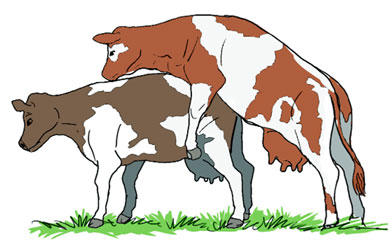

MATING

Once heat has been detected, cows should be mated.

When to serve:

Present the cow for insemination at the right time to increase the chances of conception. Below is a guide as to the best time to present the cow for insemination:

| AM – PM Rule: |

| Standing heat observed: |

Before 9 am |

Late evening the same day |

| Present for insemination: |

Late afternoon or evening |

Early next morning. |

BREEDING METHODS:

Breeding can be achieved through natural service or artificial insemination, and irrespective of the method, the aim should be to achieve increased chances of conception.

Natural service:

This is where the cow is taken to a bull and left for some time for the bull to serve.

The advantages of this method are:

1. The cow has an opportunity to be served more than once; this increase the chance of conception.

2. The semen is fresh and of good quality since there is no handling.

3. Where the farmer does not own a bull, cost of service is lower compared to A.I.

Natural service has the following disadvantages:

1. Rearing a bull is not economical especially to a small holder farmer.

2. There is risk of spreading breeding diseases.

3. There is risk of inbreeding if the bull is not changed frequently.

4. There is no opportunity to select the type of bull the farmer wants.

Some tips for natural breeding:

1. Take the cow to the bull as soon as it is detected to be in heat and leave it for at least twelve hours.

2. Young inexperienced heifers should be mated with old experienced bulls.

3. Young inexperienced bulls should be given to old experienced cows.

4. The bull should be kept fit and in good health particularly the legs and feet.

Natural mating can be done in two ways:

1. Free/pasture mating: This method of mating is practiced by farmers who own bulls which run full time with the cows.

One bull can serve 20-25 cows. It has the advantage that no heat detection is required and disadvantage of lack of accurate records and possibility of transmission of reproductive diseases e.g. brucellosis.

2. Hand mating: The bull is enclosed in its pen and the cows are brought in when they show signs of heat.

Most small-scale farmers will practice this method since bulls are owned by few farmers and others bring their cows for service at an agreed fee. The advantage is keeping accurate records while the disadvantage is the farmer has to detect heat.

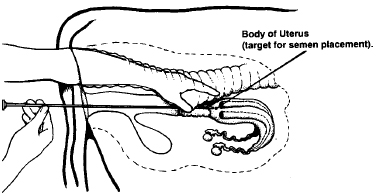

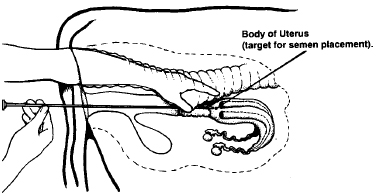

Artificial Insemination:

The process of artificial insemination starts with a healthy bull, that is disease free and producing ample quantities of high quality semen. The fertility of the cow is also important, the competency of the inseminator and a clean environment. Farmers are encouraged to use semen from proven bulls which is obtained from AI centers and registered service providers.

Advantages of Artificial Insemination:

- Prevention of venereal diseases.

- Indefinite preservation of genetic materials of low cost enabling wide testing and selection of bulls.

- Enhances genetic progress as best bulls are used widely nationally and internationally.

- Small scale farmers through AI can access good bulls cheaply.

- One is able to select the bull of interest.

- When handled properly, there is no chance of spread of breeding diseases.

- It is easy to control inbreeding.

- A.I. is the best method of improving the genetic make-up of local breeds because it enables semen from the very best bulls to be widely available.

- It is cost effective since the farmer does not have to rear a bull.

Disadvantages of AI:

- It requires very accurate heat detection and proper timing of insemination for greater chances of conception.

- The inseminator must be trained on the technique.

- It requires high investment in equipment.

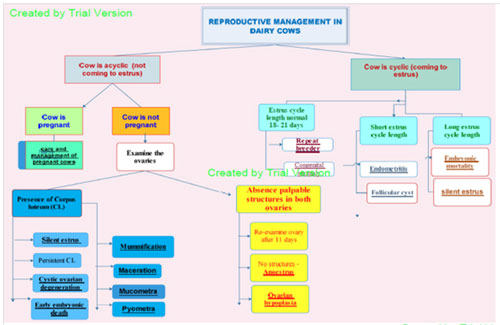

REPRODUCTIVE MANAGEMENT IN DIARY COWS :

- Reduced fertility is one of the commonest reasons for vets being called onto dairy farms.

- Most of these are indeed “normal” since, assuming no cows are culled after earlier services, then even in a herd with every cow becoming pregnant at a rate of 50% (a good rate for our dairy farms these days) there will be 12.5% of cows presented for a 4th service.

- However, in some cases there is an underlying problem reducing the chance of the cow getting pregnant. These may be either cow factors that require ultrasound examination or even other more sophisticated tests e.g. oviduct patency, or the result of a wide range of external factors, such as poor management.

- An obvious example is inefficient estrous detection. Such cows get lumped together as having ‘repeat breeding syndrome’.

REPRODUCTIVE MANAGEMENT OF PREGNANT COW :

- Pregnant animals should be watched carefully, particularly during the last stages of pregnancy to avoid abortion due to fights or other physical trauma.

- During early stages of pregnancy, there is no need of special feeding for heifers. During last three months of pregnancy when foetal growth is very rapid, a special pregnancy allowance of about 1-2 Kg of concentrate should be offered.

- Special care should be taken regarding mineral and vitamin deficiencies because they can have a serious adverse effect on the newborn calf.

- During the last few weeks of pregnancy there is a tendency of prolapse of vagina which may be caused by constipation, mineral deficiency and debility. Balanced and laxative rations should be fed to maintain the normal tone of the reproductive tract.

- Sometime udder oedema occurs before calving. This can be avoided by moderate exercise for a half an hour, two to three times per day.

- Isolate the pregnant animal 8-10 days before the expected date of calving.

- Calving areas should be landscaped to allow for adequate drainage. Shade structures are recommended.

- Calves are usually born without assistance. Any abnormality in their presentation requires immediate attention.

- After removal of calf, milk animal it will help in removal of placenta.

Placenta is normally expelled within 2 to 6 hours after calving. If placenta fails to be expelled with 12 hours it is considered retained placenta. In case of retained placenta veterinarian should be called for its removal.

- After normal birth, the dam is alert and willing to eat and drink within one or two hours of calving.

Warm water and some wheat bran should be offered to dam after calving.

- Animals having health problems should be identified and treated accordingly, whereas healthy animals can join the general population 3 to 4 days postpartum.

APPROACHES IN ACHIEVING BETTER REPRODUCTIVE EFFICIENCY IN CATTLE :

Steaming up:

- During the last two months of pregnancy, the feeding regime can affect milk production during the first lactation.

- The exact amount of concentrates to feed before calving will depend on forage quality, size, and condition of the heifer.

- A rule of thumb the heifer should be fed concentrate at 1 percent of body weight starting about 6 weeks before calving with a ration balanced in protein, minerals, and vitamins.

- Feeding concentrates allows the rumen bacteria to get used to digesting high levels of concentrate, which is very important during early lactation.

- If practical, concentrates should be fed in a milking parlor as this accustoms the heifer to the milking parlor.

REPRODUCTIVE MANAGEMENT OF PREGNANT BUFFALOES :

Males:

- Bulls reach sexual maturity at two to three years of age.

- Semen is produced all year round but it is highly affected by heat stress and low quality feed.

- The buffalo bull seems to be most fertile in spring, when the volume of ejaculate and sperm concentration is highest.

- Sperm vitality is also much higher in spring than at other times of the year. Corresponding values are lowest in summer time.

- Heat stress may have a negative effect on libido.

Females:

- Wild or feral female buffalo reach sexual maturity at two to three years of age. Domesticated buffalo that are cared for and fed properly may reach puberty earlier. Puberty is highly affected by management factors.

- Size is more important than age, and a Murrah heifer should weigh around 325 kg at insemination or mating and 450 to 500 kg at her first calving.

- The age of puberty in buffalo is 36 to 42 months in India.

- Delayed puberty in both male and female buffalo is common in India. This is due to neglect of calves during their growing period.

- In a majority of dairy buffalo calving occurs at four to six years of age. This is mainly due to an inadequate supply of feed and nutrients during the growing phase.

The reproductive cycle of a buffalo:

The oestrus cycle varies between 21 and 29 days depending on breed. The total duration of oestrus is usually 24 hours but varies from 12 to 72 hours. The most reliable sign of oestrus is frequent urination.

The signs of oestrus are much less pronounced in buffalo than in cattle. Many buffalo show oestrus only at night time, and then it is difficult to detect. A lactating animal may have a slight decrease in milk yield when in heat, although it is seldom as pronounced as in cattle. The buffalo may be more restless and be difficult to milk.

- Age at puberty: 36 to 42 months

- Length of oestrus cycle: 21 days

- Duration of heat: 12 to 24 hrs

- Time of ovulation: 10 to 14 hrs after end of oestrus

- Period of maximum fertility: last 8 hrs of oestrus

- Gestation period: 310 days

- Period of involution of uterus: 25 to 35 days.

Reasons for poor reproductive performance in buffaloes:

1. Climate affects both production and reproduction in all farm animals. However as

buffaloes are very susceptible to extreme conditions of heat and cold they show a tendency towards better performance during the cool months. In India 70 to 80% of buffalo conceive between July and February.

Buffalo are sexually activated by decreased daylight.

2. As mentioned earlier buffalo have poor thermal tolerance on account of an under developed thermo regulatory system and are unable to get rid of excess body temperature.

If their housing is not designed to take care of this special species-specific requirement for adequate shade and ventilation, it will affect production and reproduction.

3. Nutrition plays a major role in the reproductive performance of buffalo, as with other farm animals. However there is a strong possibility that the consequences of poor nutrition are often interpreted as seasonality of breeding in buffalo.

A very low protein diet can cause cessation of oestrus.

4. One of the reasons buffalo suffer from long post-partum anoestrus is because their natural behavior of rolling in dirty water pools, and unhygienic shed conditions, cause buffalo to suffer from a high incidence of endometritis.

Approaches for improving reproductive efficiency:

1. Providing the right kind of housing for buffalo to suit their natural requirements is important for their optimum performance. Free stall as well as tied systems work well for buffalo.

2. Showers or foggers with fans or wallowing tanks should be made available to buffalo during the hottest part of the day. Thermal ameliorative measures such as sprinkling and cooling are known to increase comfort levels and feed intake in buffalo.

3. Balanced feeding with mineral supplements, plenty of green fodder, and concentrate as per each animal’s specific need, is necessary to bring buffalo into normal reproductive cycles.

4. Regular testing of all buffalo and bulls for infectious reproductive diseases like brucellosis and regular culling of infected animals are crucial for good reproductive health in the herd.

5. Wall charts, breeding wheels, herd monitors and individual buffalo records are important detection aids.

Breeding of buffalo:

1. Calving interval: Calving interval in buffalo is highly dependent on management, climate and nutrition. A shorter service period will lead to a shorter calving interval – a calving interval of less than 410 days is recommended.

2. Natural mating: Except for a very small percentage of the world’s buffalo, most are bred through natural mating. In most cases at the village level and in the home tracts of buffalo there is no information on the buffalo bull or on the dam’s milk yield, and this information is seldom considered while breeding.

Utility of breeding buffalo bull:

- Having a breeding bull with the dams all the time enhances the chances of fertile mating.

This bull seldom misses a female in heat.

- However, to be able to calculate the time of calving it is advisable to keep some sort of record of expected heat.

- The observant farmer will soon learn how his buffalo behave when in heat and when to expect conception and calving. The females can be teased with a bull twice a day around expected oestrus.

- A breeding bull can be put into service from three years of age. One bull, if managed correctly, can serve 20 to 25 females.

- On a smaller farm, the bull should be exchanged more often to avoid interbreeding.

- If the bull shows signs of loss of interest in the females or is otherwise ill, he should be taken out of service immediately.

- In order to perform best, bulls must be fed high quality feed and be protected from heat and cold stress in the same way as the rest of the herd.

- Bulls should not be used for service more than twice a week.

3. Artificial insemination (AI):

With the help of AI improved genes are transmitted to a large number of offspring, and the interval between generations is reduced. Buffalo generally have more difficulty conceiving by artificial insemination than cattle do.

SOME COMMON REPRODUCTIVE DISORDERS:

1. Early embryonic death:

- Embryonic mortality is generally defined as loss of the conceptus which occurs during the first 42 days of pregnancy, which is the period from conception to completion of differentiation when organ systems develop.

- Approximately 30 percent of all embryos and foetuses will not survive to birth.

- About 80 percent of this loss occurs before day 17, 10-15 percent between day 17 and 42 and 5 percent after day 42.

- These losses to be much higher in "repeat breeders" those cows and heifers inseminated three or more times.

Causes:

- Heat Stress: This has been a serious problem affecting reproductive performance this spring and summer.

- Chromosomal abnormalities are known to be a cause of embryo mortality. Unfortunately, this problem cannot be controlled through management.

- Nutritional factors have been shown to contribute to low conception rates resulting from embryonic mortality.

- Abnormal hormonal situation such as reduced progesterone secretion or ovulation of a defective oocyte has not been determined.

- Infectious agents adversely affecting reproduction are : Corynebacterium pyogenes, Campylobacter fetus (Vibriosis), Haemophilius somnus, Leptospirosis, Neospora and the viruses bovine virus diarrhoea (BVD), infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR) and to a lesser extent Ureaplasma and Mycoplasma.

- Subclinical mastitis and other systemic infections can substantially increase the incidence of early embryo loss. Furthermore, nutritional deficiencies or an environmental challenge can alter uterine immune function.

2. Pyometra:

Pyometra (open)

|

Pyometra is characterised by a progressive accumulation of pus in the uterus and by the persistence of functional luteal tissue in the ovary.

Causes:

- In most cases, pyometra occurs as a sequel to chronic Endometritis.

- The second main cause of pyometra is the death of the fetus.

- Venereal infection with organisms such as Trichomonas fetus, which cause embryonic death, also causes pyometra.

Signs & Symptoms:

- Cows which suffer from pyometra show few or no signs of ill health; the main reason for them being examined is the absence of cyclical activity, or, perhaps, the presence of an intermittent vaginal discharge.

- The uterine horns are enlarged and distended, quite often to an unequal degree, owing to incomplete involution of the previously gravid horn or to recent conceptual death.

Differentiation of pyometra from a normal pregnancy can sometimes be difficult, but there are a number of distinguishing points:

- The uterine wall is thicker than at pregnancy.

- The uterus has a more ‘doughy’ and less vibrant feel.

- It is not possible to ‘slip’ the allantochorion.

- In most cases of pyometra, no uterine caruncles can be palpated. However, when the infection occurred in a non-involuted uterus, involution of the caruncles is delayed and they may remain palpable for quite a long time.

- Transrectal ultrasonography will demonstrate the absence of a fetus and the presence of a ‘speckled’ echotexture of the uterine contents compared with the black anechoic appearance of normal fetal fluids.

3. Repeat Breeder cow:

- To identify repeat breeder cows you need two things: good records and good heat detection.

- Given what has been said above and that on many farms the efficiency of oestrous detection is less than 60% (i.e. for every 10 cows potentially cycling only 6 are served) it can be seen that this is quite a need.

- However if done well they allow the farmer or herdsperson to pick up

cows that are cycling normally but not getting pregnant or most importantly those not fitting a normal pattern.

- Other aids, such as beacons, tail paint pedometers and milk progesterones can also improve heat detection but there is still no really cost effective substitute for the astute observer apart from the bull. Even the latter can be overwhelmed if there are too many cows in season at one time.

Causes:

Treatment:

- Improved nutrition.

- Suspect for Trichomoniasis and Vibriosis and treat them.

- Inj. Buserelin, 11 days after insemination is known to improve embryo survival.

4. Anovulation:

Ovum not released from ovary. The animal has normal cycle, normal reproductive tract but fails to conceive.

Causes:

- Inadequate level or absence of Luteinizing Hormone.

- Ovaro-bursal adhesion. It may be diagnosed by palpation of matured Graffian Follicle on the ovary more than 48hrs after the end of estrum.

Treatment:

- L.H preparations (HCG- Human Chorion Gonadrotropin)- 3000 IU. I/V. when the animal is in heat.

- Inj. Buserelin - 5 ml I/m.

- Improved feeding.

5. Delayed Ovulation:

Ovulation takes place 48-72 hours after the onset of oestrus but the spermatozoa would be dead by then.

Cause:

Treatment:

6. Endometritis:

- Endometritis is an infection of the uterine endometrium.

- Cattle endometritis is a common condition that is known by the layman as 'whites'.

- It occurs three weeks or more after calving and should not be confused with the more severe condition of metritis which occurs immediately post-partum.

- The main consequence of endometritis is poor fertility.

- It is reported to have an incidence of between 10-15 percent in dairy herds however it is very variable from herd to herd), with the total cost of Rs. 1600/- per case.

Cause:

- The main bacteria involved in endometritis is Actinobacillus pyogenes, however, numerous gram-negative anaerobes may also be involved.

- The presence of these opportunistic bacteria can delay return to service and cyclical activity, prevent fertilisation and cause early embryonic death.

Signalment: Endometritis can occur in any cow post-partum however incidence is increased by the following predisposing factors:

- Retained foetal membranes

- Dystocia

- Caesarian section or assisted calving

- Induced parturition

- Still Birth

- Twins

- Unhygienic calving environment - includes seasonal effect as indoor calving has higher endometritis rates.

- Ovarian inactivity

- Parity

- Concurrent disease and nutrition - fatty liver disease and hypocalcaemia are reported to increase endometritis rates.

Clinical Signs:

- Mucopurulent vaginal discharge should be evident on vaginal exam 21 days or more post-calving.

Discharge is relatively odourless (dependant on severity) and whites in colour, hence the name 'whites'.

- The discharge should not be confused with lochial discharge or vaginitis.

- Rectal palpation should reveal a poorly-involuted, oedematous uterus.

- On an individual or herd level there may be a history of subfertility.

Diagnosis:

- Diagnosis should be based on the calving history and clinical signs following vaginal and rectal exam.

- Vets may use a scoring system to categorise the colour and odour of the vaginal discharge which indicates how severe the infection is and whether treatment is necessary.

- Measurements of the uterine and cervical diameter may be included in the scoring system. Definitive diagnosis can only be achieved by endometrial biopsy, however this is rarely indicated.

Treatment:

- Antibiotics: Ideal antibiotics are cephalosporins and oxytetracycline as they match the majority of criteria listed above.

Metranidazole and chloramphenicol should not be used as they are banned from use in food-producing animals.

- Hormones: Prostaglandins, PGF2a or analogues can be administered parenterally. They should be considered the treatment of choice if a corpus luteum is present. There is no milk withdrawal period for prostaglandins, making them ideal for use in dairy cattle. These are mainly used in chronic cases.

- Antiseptics: Chlorhexidine and metacresol sulphonic acid (Lotagen), povidone iodine antiseptic administered intrauterine.

7. Silent heats (unobserved and subestrus):

- Incidence of subestrus in cattle and buffaloes has a wide variation in the frequency (15 - 73%).

- The intensity of heat signs in buffaloes is generally lower and also homosexual activity is not pronounced as in cows.

- The intensity of expression of estrus is generally affected by housing, floor surface, yield, lameness and number of herd mates in estrus simultaneously.

- Summer anestrous is an important condition is buffaloes contributing to infertility in buffaloes.

- Heat stress has a pronounced effect on the estrus behaviour of the female animals as heat stress reduces the length and intensity of estrus.

8. Dystocia :

Dystocia

|

9. Retention of placenta :

Retention of placenta

|

10. Prolapse :

Prolapse

|

11. Anoestrus:

- Anoestrus is the failure of a cow to cycle and display oestrus (heat).

- Anoestrus is normal before puberty, during pregnancy and for a short period after calving (postpartum anoestrus, PPA).

- All cows undergo varying degrees of PPA.

Causes:

- Factors responsible for anoestrus are environmental stress, endocrine, nutritional (negative energy balance, micro and macronutrient deficiency), managemental factors such as lactational stress, suckling etc.

Diagnosis:

Anoestrus may be diagnosed by per-rectal palpation of reproductive organs and frequent activity of reproductive cycles of buffaloes using ultrasonography.

Negative energy balance; a cause of anoestrus:

NEB happens when energy intake is lower than output in milk production and maintenance. It is seen as a loss of body condition as body fat is mobilised to meet the energy demands of lactation.

Some degree of NEB is inevitable in nearly all dairy cows in the month after calving. Resumption of cyclic activity after calving is influenced by:

- nutrition

- body condition

- suckling

- lactation

- breed

- age

- uterine pathology

- debilitating disease

Fewer than 10% of cows fail to ovulate in most well-managed dairy herds by day 40 post partum. It is well established that poor nutritional status and Negative Energy Balance are responsible for the majority of anoestrus cases in both dairy and beef cattle.

Treatment of anovulatory/anoestrus conditions in cattle:

Treatment is based on:

1. Improvement in energy status: optimal nutrition during the transition period and during early lactation.

2. Hormonal treatments: combined with increased energy supplementation or reduced suckling stimulus may also help to stimulate oestrus.

Techniques for enhancing reproductive efficiency in dairy animals:

For improving fertility of the herd so many tools were in practice since last fifty years, and many will be added in times to come - these tools are:

1. Use of artificial insemination technique.

2. Use of frozen semen.

3. Use of high quality, progeny tested bull's semen.

4. Improving different managemental practices like -

- Maintenance of good health record/breeding records.

- Offering balanced and nutritious fodders and feed.

- Breeding at proper time.

- Use of heat detection methods.

- Doorstep services of A.I.

Now days in most of the western developed countries where dairy development has reached to its peak, many new technologies are in vogue, these are -

1. Oesturs synchronization.

2. Embryo transfer.

3. Early pregnancy diagnosis tests.

Culling of Unproductive Dairy Animals:

Dairymen should develop a checklist of culling reasons to use in their decision making process. The following list of 10 questions is one that could be used for each cow before deciding her future in the herd.

- Is her yearly production 20 per cent or more below the herd's rolling average?

- Is she a chronic mastitis case? Check this one closely, because a cow with chronic mastitis is producing below her capability and, in addition, could be spreading mastitis to other cows in the herd through the milking equipment.

- Will she be dry four months or more? Long dry periods are costly to the dairyman and may indicate the cow has a problem of becoming pregnant, a trait not desired.

- Is she a hard milker? Is her udder shape or teat structure such that she is a nuisance to milk?

- Does she have a history of calving difficulties or post calving illnesses such as retained placenta, metritis, or milk fever? Cows that cause problems at calving time are not pleasant to have and are costly to keep in the herd.

- Does she have an undesirable disposition?

- Is she a nervous cow or does she kicks whenever her udder is touched? These are undesirable traits that should be noted along with production and calving problems.

- Is she below the herd's average body type? Check body confirmation to see if it comes up to specifications for the herd.

- Is she a timid cow? With the type of dry lot housing systems most dairymen have today, timid cows usually will not get the amount of feed required to be high producing animals.

- Is she an old cow, and is the available barn space needed for freshening heifers? Fresh heifers usually have a higher genetic potential for milk production than older cows, especially if a progressive A.I. program is used in the herd.

A yes answer should probably be given to at least two questions before making the cow a strong candidate for culling. In many cases, though, one reason may be enough justification to base a culling decision. Besides using a checklist in making culling decisions, other facts should be considered.

Culling should be based on the evaluation of the following:

1. First-calf heifers:

Undersized heifers will probably produce less milk the first lactation because of their size. This situation is an indictment of the dairyman's heifer feeding program and not necessarily the producing potential of the heifer.

2. Stage of gestation: Extremely long calving intervals can be costly. With other factors being equal, cows in mid-lactation with several months to go before freshening are better prospects for culling than cows that will freshen sooner and return to peak production sooner.

3. Mastitis:

Cows with CMT scores of 2, somatic cell counts of 1.2 million or greater, should be culled before other potential culls because they are potential sources of intra-mammary infections of other cows.

4. Age:

Other factors being equal, cull older cows before younger cows of comparable relative value. The genetic potential of younger animals should be greater than that of older animals, so keeping the younger cows in the herd longer should be a sound practice.

5. Past performance:

Given two cows with the same relative value and other factors equal, cull the cow first that has the lowest previous production records.

Past performance can be suggestive of future potential. Management errors in the current lactation could adversely affect a cow's performance.

|

|

| Back |

|

|

Developed by :

|

|

♦ Dr. Pranav Kumar (Assistant Professor) |

♦ Amandeep Singh |

♦ Jaspal Singh |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Scroll

|

Division of Veterinary and Animal Husbandry Extension Education

Faculty of Veterinary Sciences and Animal Husbandry, R.S. Pura, SKUAST Jammu |

|